E-mail: jay(at)salsburg(dot)com

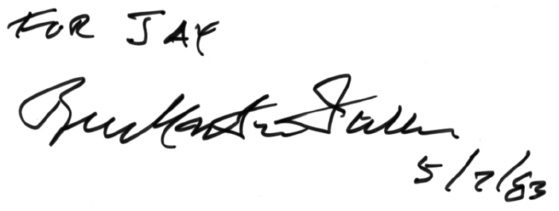

Anne & Buckminster Fuller

March 15, 1981

In search of a better world, they put their faith in the power of the

mind.

by Stacey Peck

photographs by Suzanne Murphy

A man and his media

Anne and Buckminster Fuller

Anne and Buckminster Fuller

Click here for hi-res image!

Bucky flying high over his development

Bucky flying high over his development

Click here for hi-res image!

Always comfortable in the spotlight, Buckminster Fuller supervises the construction

of his Fly's Eye dome in Pershing Square (Los Angeles, CA) while local newscasters

watch him.

John and Bucky studying their accomplishment

John and Bucky studying their accomplishment

Click here for hi-res image!

Dome supervisor John Warren confers with Bucky as they direct the installation

of the dome's bulbous windows.

The Fly's Eye Dome

The Fly's Eye Dome

Click here for hi-res image!

Later termed a "mushroom with warts"

by the Los Angeles Time's architectural critic John Dreyfuss, the design

provides a fine muted light for the photographic display housed inside.

Bucky's watch chain

Bucky's watch chain

Click here for hi-res image!

A Fuller trademark, Bucky's watch chain is adorned with natural crystals

collected on his travels, his Phi Beta Kappa key and a miniature geodesic

dome.

Jamie and Bucky

Jamie and Bucky

Click here for hi-res image!

Jamie Snyder, Bucky's grandson and confidant, interviews Bucky for the press.

During his 85 years Buckminster (Bucky) Fuller has been labeled a crackpot

and a genius, but he has never been ignored. A designer, philosopher, inventor,

poet, he has won numerous awards for contributions to architecture and design.

Fuller has been awarded 39 honorary degrees from universities throughout

the United States and England, and has written 19 books and 115 major articles.

Yet he never got past his freshman year of college.

Bucky and his wife, Anne, are both descendants of America's first families.

His father, a Massachusetts leather merchant, died when Bucky was 12. After

attending Milton Academy, Bucky entered Harvard and encountered problems;

his Milton class mates would not associate with him because he was not invited

to join a club. "The club system was only for very rich people,"

he says, "and as I was not rich, I felt out of place. When I found

out my friends felt sorry for me I couldn't stand it. I began cutting classes

and going to New York, where I hung around the stage doors of popular Broadway

shows. I used my Russian wolfhound as bait. and when the girls stopped to

pet the dog, I became acquainted with them. When I cut my exams to see dancer

Marilyn Miller, I made a great hit with my classmates but not with the Harvard

officials, and they asked me to leave."

In 1914 Bucky met beautiful Anne Hewlitt, daughter of prominent New York

architect James Monroe Hewlitt. "I thought he was very nice,"

says Anne, "but we all had lots of beaus then. And everybody knew the

war was coming so it made us a little more serious and a little more gay

at the same time. We felt we should have fun while we could." They

married in 1917, and Bucky joined the Navy.

After the end of the war he worked for a meat packing company in New York,

then went into the building business with his father-in-law. Shortly after,

the couple's first daughter, Alexandra, became ill and died, and the company

failed after constructing 240 homes. "I wasn't a businessman,"

he admits, "and by the time our second child, Allegra, was born in

1927, we were penniless. I decided I'd better get out of the way, because

I was a disgrace to my family and would never make any money."

Instead of committing suicide as he had intended, Bucky decided to use his

accumulated experience for the benefit of others. In 1928 he designed a

single-family house with rooms hung from a central mast that could be easily

moved if the owner wanted to change locations. It was air-conditioned, and

featured a nearly waterless bathroom with a 10-minute bath supplied by a

fog gun. When a scale model was displayed at Marshall Field's department

store In Chicago, it was christened Dymaxion combination of dynamic and

maximum. The word became Bucky's personal trademark.

In 1932, he designed the three-wheel Dymaxion car. The steering wheel was

connected to a single rear wheel, enabling the car to circle within a small

radius. It could run at 120 miles per hour when equipped with a standard

Ford 90-horsepower engine. In 1938, an accident unrelated to the car's design

killed a passenger and Bucky abandoned both the Dymaxion house and car,

unconventional ideas during a very conventional time, had attracted the

nation's attention. His fame led to jobs as assistant director of research

and development at the Phelps Dodge Corp. and as technical consultant to

Fortune magazine. Again captivating the public consciousness, he created

the Dymaxion Airocean World Map in 1934. It showed the world as a flat surface

without distortion, and was the first map to be granted a U.S. patent.

Bucky next returned to an idea he had first developed during the 1920s-the

geodesic dome. Eventually the Ford Motor Co. commissioned him to build a

dome over its Dearborn plant rotunda. A request from the Marine Corps for

a plastic and fiberglass enclosure that could be delivered by a helicopter

followed in 1954. And in 1959 the dome served as the stage for one of the

decade's great media spectaculars, the Nixon-Kruschev kitchen debate. Another

now houses the Bicentennial information and exhibition center in Los Angeles'

Pershing Square.

Financially secure, Bucky was able to turn his attention to writing. In

1961 Harvard named him Charles Eliot Norton professor of poetry; three volumes

of verse followed. The Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1970) found

a receptive audience in the ecologically minded college students who empathized

with his theories of universal interdependence. And In 1975, Bucky published

what many consider his major theoretical work, Synergetics: Explorations

in the Geometry of Thinking.

Today he works as hard as ever on developments to enhance the environment,

recently committing himself to more than 20 speaking engagements within

a period of eight months. He and Anne live near their daughter and two grandchildren

in Pacific Palisades, CA, and spend a portion of each summer in their house

on one of the islands off the cost of Maine.

Q. What has it been like living with Bucky Fuller for years?

Anne. I have really enjoyed it. He's a great worrier, all these tremendous

problems are on his mind and some of them weigh very heavily. But my mind

is not that way; I'm more cheery and not too concerned with weighty problems.

I realize there's not much I can do about them, so my philosophy is to enjoy

life.

Q. You've often talked about the lag between invention and acceptance. Why

is that?

Bucky. Nature takes time. For example, It takes nine months to make

a human baby and there are all kinds of gestation rates in the animal kingdom.

In the world of electronics, where Invisible electromagnetic waves move

at 186,000 miles per second, there is only a two-year lag between invention

and its industrial use. In aeronautics, where you move about 1,000 miles

per hour, there is a five-year lag. And that is desirable. It takes time

to prove that something is safe.

We can see the second hand on a clock moving, but we can't see the minute

hand move. When you can't see something move, you don't get out of the way.

The faster a thing moves, the more chances you have to see what is wrong.

So we find that in a single-family dwelling there is at least a 50-year

lag because of the least visibility of motion.

Q. But wasn't the geodesic dome accepted very quickly?

Bucky. Oh yes, but that was only a demonstration of my structural

principle for the single-family dwelling. The Dymaxion house, an autonomous

dwelling with no plumbing, no water pipe connections, has still not been

accepted. But its time has come because now, in addition to having a critical

housing shortage, people can no longer pay for their utilities.

Q. Why did you and Anne leave the dome in which you were living in Carbondale

Illinois?

Bucky. Because my number one concern is not me. I travel 90 percent

of the time and have to leave Anne alone. Now, when I'm away, Anne is near

Allegra.

Anne. We enjoyed living in the dome. It was easy to take care of, and even

though it was only 1,000 square feet, it seemed like a big house and we

didn't feel closed in. We had a foyer, two baths, a kitchen, a dining room,

an enormous living room and a library upstairs.

Q. Have you felt hampered by the lack of a college education?

Bucky. No, never. I developed my own knowledge of physics and mathematics.

In fact, I feel that most scientists are still in the dark ages. In 1953,

when I lectured at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology faculty club,

there were about 300 scientists in the room and I asked, "Is there

anyone present who has not seen the sun go down?" There were no hands

raised and I was shocked. I said, "You have known for 500 years that

the sun does not go down and yet you have done absolutely nothing as educators

to coordinate your senses with your knowledge. When you tell your children

to look at the sun going down, you are deceiving them. What kind of educators

are you?''

Q. Does our educational system hinder original thinking?

Bucky. No question about it. Every child is born to be a comprehensivist.

The mind deals with what you can't see as well as what you can. But how

do we teach the children? When a child asks, "Why do the galaxies do

what they do?" the daddy answers, "Wait until you get to school."

Then the school says, "Never mind about the universe. Let's talk about

whether you're going to get an A or a B or a D."

We have learned in biology and anthropology that extinction has been the

consequence of overspecialization and our specialization is leading to extinction

of the species. The only thing humans need is the ability to think. Unfortunately

they think mostly about how to make a living and get along in the system

rather than about what the universe is trying to tell us.

A newspaperman wanted to know how I interacted with children, so he brought

two boys, 11 and 12, and a 10 year-old girl to our house. They had read

some of my books before they met me. I asked the 12-year-old what he was

most interested in and he said he wanted to be a magician. The 11-year-old

was interested in electronics, but the girl said, "I am a comprehensivist

like you. I am interested in everything."

It's interesting that the first two were born before we got to the moon

and the girl was born after. When I was born, you would have been called

a lunatic if you said we could touch the moon. This is a completely new

world. When we got to the moon, we saw ourselves for the first time and

that made a big change in the attitudes of the young. I've gotten many letters

from 8 and 10-year-olds saying "Humanity can do anything it wants to

do. Why can't it make this earth work?"

Q. You've said that you look to the young people to improve world conditions.

We were all young at one time. Why didn't we do it?

Bucky. Because each successive child is born with a little less misinformation

and conditioned reflex. I was told by grown-ups that it is inherently impossible

for man to fly. Then the Wright brothers flew. I was told man would never

reach the Poles. When I was 14, man got to the North Pole and when I was

16, he got to the South Pole. Now we have a little girl who was born after

man went to the moon and she has absolute confidence that we can solve any

problem by using the mind and perseverance.

Q. What do you feel has been your most significant contribution to society?

Bucky. Knowing ways to catch myself telling a lie to myself. But

I never try to reform anybody else. We are born naked and helpless and are

driven to learn by trial and error. We make mistakes, but that is healthy

if you have the courage to admit you've made a mistake. I'd like to be remembered

as an average, healthy human being who used what humans are given for the

advantage of others.

Buckminster Fuller dead at 87

July 2, 1983, Los Angeles, California

An architect, inventor, writer, futurist, high priest of technology and

a college dropout died yesterday. They were all Richard Buckminster Fuller,

and he was 87 years old.

Fuller, who devoted himself to saving the world with technology, died at

4:50 pm. of a heart attack at Good Samaritan Hospital as he visited his

critically ill wife, Anne, who is a patient there, said a hospital spokeswoman.

"It was very sudden," said the spokeswoman, who asked not to be

identified and declined to discuss the specifics of the wife's illness.

"She is extremely old and very ill, and he was visiting her."

Although Fuller, who lived in Pacific Palisades, was hailed by some near

the end of his life as "the greatest living genius of industrial-technical

realization in building," many others-through most of his life-called

him a crackpot.

That label came from inventing such things as houses that could fly, bathrooms

without water, strangely folded maps and ways of living bearing the mysterious

word "Dymaxion," for designs called "octet trusses,"

"synergetics" and "tensegrity spheres."

He even envisioned our planet as a ship traveling in space, and warned that

"Spaceship Earth" was doomed if people failed to make use of technology.

For example, his famous geodesic dome was designed to cover a maximum space

with a a minimum of materials, lightweight and inexpensive.

"Personally, he was a man of integrity because of how he led his life,

how he carried himself throughout his life, all 87 years," said Jeff

Milch, a worker at the Friends of Buckminster Fuller Foundation in Pacific

Palisades, which strives to apply his ideas to practical use.

During the 1970s, Fuller averaged nearly 100 speaking engagements per year,

while continuing to write, consult and design. (Some estimates placed his

yearly earnings as a lecturer at $180,000).

The 5-foot 2-inch Fuller once said of himself in this way: "I am not

a thing-a noun. I seem to be a verb, an evolutionary process-an integral

function of the universe."

The Fuller process began in Milton, Mass., on July 12, 1895, when he was

born to the wife of a Boston merchant. A great aunt was transcendentalist

Margaret Fuller, the literary friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson and discoverer

of Henry David Thoreau.

He continued a five-generation family tradition by attending Harvard, but

he never made it through the first year. He felt he was a social outcast

when no one would room with him. So, he once said, he "deliberately

set out to get into trouble." Harvard officials suspended him twice

before expelling him.

Shortly after his 1917 marriage to Anne Hewlett, daughter of a prominent

New York architect, he joined the Navy. He showed such promise he was commissioned

an ensign and sent to the Naval Academy to study. After World War I, he

and his wife moved to Chicago, where he worked for a company marketing building

materials invented by his father-in-law.

In 1927, he attempted suicide (which later became one of his most moving

tales while on the lecture circuit). He was still distraught over the death

of his young daughter, 4-year old Alexandra, five years earlier, was unemployed,

drinking heavily and had just lost some of his friends' money on an abortive

business deal.

At that point he couldn't t imagine earning a living because he viewed individual

survival as a function of depriving others --the antithesis of his basic

philosophy. He resolved to jump into Lake Michigan and end his sorrow and

the humiliation of his family, including a new born daughter, Allegra.

He changed his mind only when he became convinced that his original way

of thinking was right: that the human species should be a cooperative society

and that sensitivity is to be highly prized. Hence, it was not the species

but the system that was at fault.

"I decided to commit myself to an experiment," he said during

a 1979 lecture at Pasadena's Art Center School of Design. "I decided

to find out what an unknown individual might be able to do on behalf of

humanity that great nations and private enterprise cannot do. And I'm still

finding out."

After inventing an apartment house built of lightweight alloys that would

be so light it could be carried by a dirigible, he next designed a lightweight

single-family home, whose rooms also hung from a central mast for easy relocation.

The house had a molded bathroom unit that was nearly waterless, using only

a quart of water for a 10-minute bath by means of Fuller's fog gun. Publicists

coined the name "dymaxion" for the house-from "dynamic, maximum

and ion"-for an exhibit in 1928 at Chicago's Marshall Field's department

store.

In 1930, he and his family moved to New York's Greenwich Village, where

he resurrected the Greek word "ecology" and published Shelter

Magazine for two years, a forerunner of environmental concerns.

During World War II, he worked for the U.S. Board of Economic Welfare, converting

grain silos into military housing units.

In 1949, he conceived the geodesic dome that forever changed his image as

a lovable crackpot when architects called it a genuine advance. He patented

the dome in 1954, and at last count, more than 200,000 had been built throughout

the world.

Anne and Buckminster Fuller

Anne and Buckminster Fuller Bucky flying high over his development

Bucky flying high over his development John and Bucky studying their accomplishment

John and Bucky studying their accomplishment The Fly's Eye Dome

The Fly's Eye Dome Bucky's watch chain

Bucky's watch chain Jamie and Bucky

Jamie and Bucky